by

Damien F. Mackey

"And the Word became flesh and Tabernacled among us".

John 1:14

Introduction

Some non-Christians, such as the Moslem scholar Dr Ali Ataie (Christian Zionism: a Major Oxymoron), are emphasising that the Christian Zionists are going against the New Testament by hoping to hasten the end times and the Final Coming of the Messiah, Jesus Christ, by re-building the (third) Temple in Jerusalem.

For, as these non-Christians rightly say, Jesus had claimed of the old Temple that “not one stone here will be left on another” (Mark 13:2), and that He himself was now the Temple.

In this way, such non-Christians have read the New Testament far more accurately than have the Christian Zionists, who are succeeding only in emptying the Scriptures of their true meaning.

A completely new age had been ushered in with the return of Jesus, as He said, to bring fiery Justice upon the evil and adulterous generation that had crucified Him (cf. Malachi 3:5: “I will come to you in judgment ....”). The land of Israel was ravaged and burned, its capital city of Jerusalem was destroyed, the Temple was totally eradicated, and those thousands of Jews who were not killed were taken away into captivity.

That physically severed forever the ancient Abrahamic connection between the Jews and the Holy Land.

The far more important spiritual connection with Abraham, based on Faith, a pre-requisite for the possession of the Holy Land, had already been shattered. So much so that Jesus, when the Jews boasted of having Abraham for their father, insisted that the Devil, not Abraham, was the father of the prophet-slaying Jews. 'You belong to your father the Devil' (John 8:44).

Saint Paul in Galatians makes it quite clear that the connection with Abraham is only through Jesus Christ, the “seed” of Abraham (3:29): “And if you be Christ’s, then are you Abraham's seed, and heirs according to the promise”.

The straw that broke the camel's back would be the rejection of, and murder of, the Prophet of Prophets himself, Jesus the Christ.

It is sad and quite frustrating to see pious Jews now reverencing a large Roman wall situated well away from where the Jerusalem Temples had stood, and hopefully expecting the Messiah to arrive in Jerusalem in the not too distant future.

Nor is it any good that Zionists - including the Christian version of these - a very powerful and wealthy lobby, have that same goal of re-building the stone Temple (in the wrong place, it must be said), to welcome the Messiah, or Jesus (depending on whether one is Jewish or Christian).

Pope Pius X and Zionism

Does Zionism have a place?

Not according to the reaction of pope Saint Pius X, who replied to Theodor Herzl in a meeting in 1904: https://catholicism.org/the-zionist-and-the-saint.html

…. The pope was Saint Pius X. According to Herzl’s diaries, when asked to support a Jewish settlement in Palestine, the saint “answered in a stern and categorical manner: ‘We are unable to favor this movement. We cannot prevent the Jews from going to Jerusalem — but we could never sanction it. The ground of Jerusalem, if it were not always sacred, has been sanctified by the life of Jesus Christ. As the head of the Church, I cannot answer you otherwise. The Jews have not recognized Our Lord; therefore, we cannot recognize the Jewish people.’

That is not to say that the popes are anti-semitic, a separate issue. Pope Pius XI would remind Catholics (via a group of Belgian pilgrims) back in 1938, in the face of tyrannical pressure being exerted upon the Jews, 'We are spiritually Semites'.

And the Church favourably included the Jews (and Muslims) in the Vatican II document, Nostra Aetate.

{I have difficulty with the restriction of the term, Semitic, to merely the culturally Jewish people. Plenty of others are of Semitic origins. Added to that, we no longer know, since c. 70 AD, who of those claiming to be Jews, and who are culturally Jewish, are actually ethnically Jewish}.

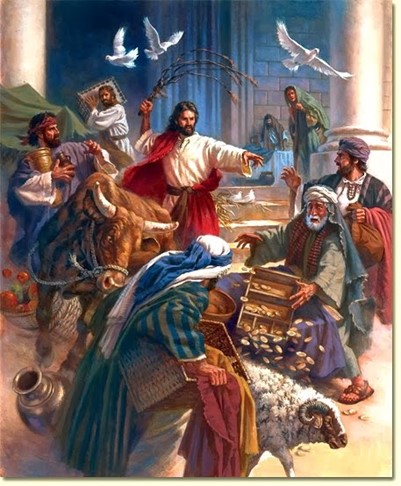

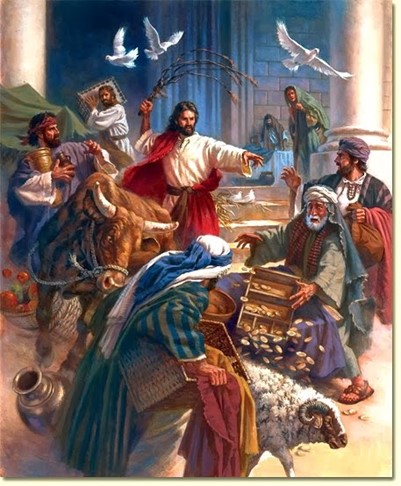

‘Destroy this Temple’

The pivotal biblical association of Jesus with the Temple was, of course, the incident of his cleansing of the sacred place from the money-changers.

This led to his assertion: ‘Destroy this Temple and I will rebuild it in three days’ (John 2:19). And, though it had taken 46 years to build the last stone Temple (2:20), the Word is timeless.

The Apostles realised that Jesus was speaking of the Temple of his very body (John 2:21-22). Jesus is the new Temple, a spiritual Temple that neither Gog and Magog, the Babylonians, the Romans, nor renegade Jewish zealots, would be able to quench. So, even if the modern Zionists do achieve their aim of building a temple complete with priests and animal sacrifices, again completely against the New Testament that has Jesus as the true High Priest (Hebrews 4:14) making the one and only sacrifice - and which temple will be situated in quite the wrong place anyway, and so not geographically legitimate - it will all be completely futile and irrelevant in the great cosmic scheme of things.

And it will not succeed in luring the true Messiah.

“Tabernacled Among Us”

No wonder that Jesus was wont to go all the way back to Moses to explain himself (Luke 24:27). His human existence, moving amongst his people, had been foreshadowed back in the time of Moses, in the Pentateuch, by the moveable Tent of Meeting, or Tabernacle.

Exodus 33:7-11:

Now Moses used to take a tent and pitch it outside the camp some distance away, calling it the “tent of meeting.” Anyone inquiring of the LORD would go to the tent of meeting outside the camp. And whenever Moses went out to the tent, all the people rose and stood at the entrances to their tents, watching Moses until he entered the tent. As Moses went into the tent, the pillar of cloud would come down and stay at the entrance, while the LORD spoke with Moses.

Whenever the people saw the pillar of cloud standing at the entrance to the tent, they all stood and worshiped, each at the entrance to their tent. The LORD would speak to Moses face to face, as one speaks to a friend. Then Moses would return to the camp, but his young aide Joshua son of Nun did not leave the tent.

Jesus, too, was often on the move among the people.

Saint John picks this up in his Gospel by likening the Word's human existence, dwelling on earth, to being Tabernacled (ἐσκήνωσεν). That is the literal meaning of the text, and it is meant to recall the Tent of Meeting which contained the glorious Ark of the Covenant with its mercy seat, the Menorah, and the shew bread.

Centuries before (cf. I Kings 6:1) King Solomon would successfully build the fixed Temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem, the Lord's dwelling amongst the people of Israel was to be, for centuries, this moveable Tent.

“Glory of the Lord”

“God was at the centre. Surrounding the Tent were the Levites. And around the Levites were the 12 tribes of Israel” (cf. Numbers 2:2). Wherever nomadic Israel was, encamped around the Tent to which were aligned the twelve tribes of Israel, there was to be seen the shining Pillar of Fire, the Kavod Yahweh, “Glory of the Lord”.

The shining Cloud is popularly (but not biblically) known as the Shekinah.

When King Solomon built the Temple of Yahweh, the Glory Cloud came and rested upon the Temple as a sign to Israel that this was where God dwelt upon earth (2 Chronicles 7:1-2): “When Solomon finished praying, fire came down from heaven and consumed the burnt offering and the sacrifices, and the glory of the LORD filled the Temple. The priests could not enter the Temple of the LORD because the glory of the LORD filled it”.

But, centuries later, after Israel had malevolently apostatised, and just prior to the first destruction of the Temple by the Babylonians, the prophet Ezekiel saw the Glory Cloud (the Lord) depart from the Temple (Ezekiel 10:18): "Then the Glory of the Lord departed from over the threshold of the Temple ...".

Israel was now on its own.

It appears that the Kavod Yahweh did not return even after the exiles from Babylon had rebuilt the second Temple, goaded on by Haggai and Zechariah. Those old enough to remember the former Temple wept (Ezra 3:12; cf. Tobit 14:5).

But the prophet Haggai - who, as I need to point out for what will follow, was Tobias (= Job) the son of Tobit, Tobias having been given the Akkadian name, Habakkuk (shortened by the Jews to Haggai) - seemed confident that Kavod Yahweh would eventually return and that the Temple in Jerusalem would be even greater than before (Haggai 2:6-7).

But this outlook has Messianic ramifications (cf. Malachi 3:1).

The alignment of the twelve tribes of Israel to the ancient Tent of Meeting, and to the later Temple built by King Solomon, anticipated Jesus and his twelve Apostles, upon whom the New Jerusalem was to be built (Revelation 21:19).

Nativity and the “Glory of the Lord”

Biblical scholars wonder: Why does Luke refer to the Shepherds but not the Magi, and Matthew, to the Magi but not the Shepherds? Some have even tried to tie together all in one the Shepherds-as-the-Magi - a thesis that had really grabbed my interest for a while.

The connecting link between Luke and Matthew here is the Kavod Yahweh.

The Magi knew that what they had seen was His star because it was the Kavod Yahweh returning to Jerusalem, as their ancestors had foretold, with the birth of the King of the Jews. What the Magi saw was the same glorious manifestation of light that the Shepherds likewise had seen at the Nativity. The Magi possibly delayed their trip significantly to allow for the Christ Child to grow and so take his rightful place seated in Jerusalem. (They would well have known from Micah 5:2, however, that the Nativity was to occur in Bethlehem).

That is why the Magi eventually headed for Jerusalem not led by the Star, which they saw again only after they had left King Herod. It led them to “the house”” (no longer the stable) (Matthew 2:9).

So, just as the Kavod Yahweh would lead the Israelites through the wilderness, and would stop wherever they needed to halt, so did the same Kavod Yahweh now lead the Magi from Jerusalem to Bethlehem, and stop. This can be no regular star because it stopped. It was a guiding Cloud of Light, the Glory of the Lord.

One could say, it follows the Lamb wherever He goes.

It was still associated with the infant Jesus when He appeared to Sister Lucia on a shining cloud at Pontevedra (Spain) in 1925, to request the Communion of Reparation (the Five First Saturdays), whose 100th anniversary we will be celebrating next year, 2025, the Jubilee Year of Hope.

The Fatima seer, Sister Lucia, described the resplendent apparition which we need to heed now as a matter of great urgency:

https://fatima.org/news-views/the-apparition-of-our-lady-and-the-child-jesus-at-pontevedra/

“On December 10, 1925, the Most Holy Virgin appeared to her [Lucia], and by Her side, elevated on a luminous cloud, was the Child Jesus. The Most Holy Virgin rested Her hand on her shoulder, and as She did so, She showed her a heart encircled by thorns, which She was holding in Her other hand. At the same time, the Child said:

“‘Have compassion on the Heart of your Most Holy Mother, covered with thorns, with which ungrateful men pierce It at every moment, and there is no one to make an act of reparation to remove them.’

“Then the Most Holy Virgin said:

“‘Look, My daughter, at My Heart, surrounded with thorns with which ungrateful men pierce Me at every moment by their blasphemies and ingratitude. You at least try to console Me and announce in My name that I promise to assist at the moment of death, with all the graces necessary for salvation, all those who, on the first Saturday of five consecutive months, shall confess, receive Holy Communion, recite five decades of the Rosary, and keep Me company for fifteen minutes while meditating on the fifteen mysteries of the Rosary, with the intention of making reparation to Me.’”

Blood and water flows from the Temple

The Passover ritual that was occurring at the Temple while Jesus, the Lamb of God, was being crucified, facing the Temple, was being enacted in his very flesh. The slaughter of the sacrificial lambs, for instance. The rending of the huge curtain of the Holy of Holies. Even the priests sprinkling the floor with blood was imaged when Judas (was he a priest?) threw the blood money across the floor in front of the priests. (Dr. Ernest L. Martin, RIP, brillianty picked up this one).

But, most significantly, the blood and water that gushed out from the side of the Temple when the priests opened a side door, at the same time that blood and water was flowing from the pierced side of Jesus on the Cross (as noted by Dr Ali Ataie, Christian Zionism: a Major Oxymoron).